It’s three a.m. Even though I had the opportunity to view the heavens as few people have ever seen, I am amazed at the amount of stars that escape the influence of the Tucson urban lights. I conclude it is another Sonora desert phenomenon. They are everywhere if you just notice. I am grateful for noticing.

The lake’s water is rippling, fed by the slight southwest breeze and enhanced by the park lamps into a million refractions. There is the usual medley of sirens, airplanes, and motorcycles from the city mixed with the calls of owls, coots, and night hawks from the desert’s edge, but essentially it is peaceful here. I interrupt its tranquility with a cast.

The snap of the wrist, the whir of the line thru the rod’s guides and the plop of the lure temporary overpower the medley. I love fishing.

It’s been like this since my youth. I remember countless mornings spent in Idaho and Wyoming, watching the world awake. I remember sunrises that defied any artist’s stroke, where it seemed there were two skies; one on top of another with colors in them that no one could name. I have snapshot memories of animals, birds, and reptiles and my encounters with them that would surpass any nature documentary. Most of all, I recall epic battles with worthy adversaries. Fishing was always good to me. It has always given me solitude without loneliness and it did not take a rocket scientist to determine that fish live in beautiful places. All I needed to do was notice.

The lake’s resident geese stir and announce a winged entry into the water with a chorus of raucous alarm. I direct my gaze in their direction. In the gloom, I see a coyote prancing, not even mildly interested in the geese.

Over the years, I developed the ability to mimic birds and animals. I learned how to purse my lips, suck in air and create a sound similar to a predator call. I could not help to give the coyote my best imitation.

Instantly, the animal freezes, peering toward the open water. My thoughts call up the fact the canines have 100 times better night vision than humans. I wonder if it can see me. I wonder what’s going on in its mind, hearing a rabbit call coming from the middle of the lake. I conclude it can’t see me. I cast a low silhouette when I am in my float tube. This is one of the reasons fishing from a float tube is so effective. Even the fish cannot see you as well as they see individuals in a boat. The animal regains purpose to his journey and leaves without a second look.

I reposition my body with my float tube’s seat. My float tube has always been an attraction to anyone on shore and in other watercraft. They would stare in silence, some would ask if my legs were in the water, others would just laugh, point me out to their children. It becomes even more atypical when I use my fly rod. I laugh that it still remains the same after thirty years. They usually stop chucking when they see me catch a fish.

It is serving me well again after years of being stored in a closet. My tube lay dormant for years while my fishing watercrafts evolved through a wide variety of boat styles and motors. It re-emerged after a required selling of my Ranger bass boat to return to college and my self imposed fishing sabbatical while I finished my educational goals. Soon after I started my second career, my association with my tube was reborn.

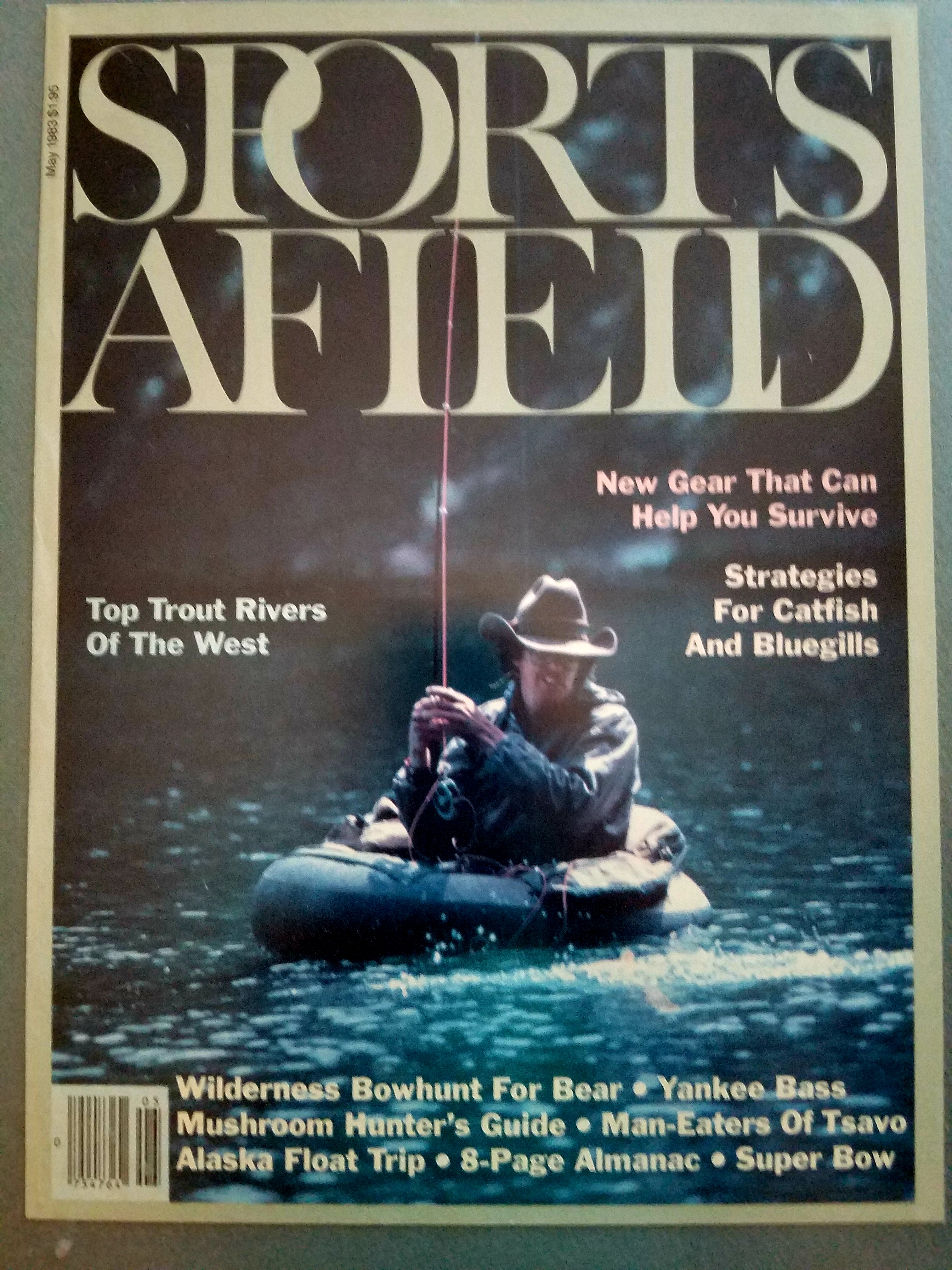

I feel like I have come full circle as I return to my old way of fishing. I cannot help remembering that day when my picture was taken by my good friend Tom Montgomery. Being a professional photographer, he sold that print to “Sports Afield” as a cover photo.

I was a cover boy. It was start of a long relationship I had with every form of media. I enjoyed that attention, but now I am just a simple man, relieving stress, enjoying the Arizona summer morning.

The water feels cool around my wader protected legs. It is serene and there is no human audience present in the early Tucson morning. The army of arm chair fishermen and the families picnicking will arrive later this weekend morning. Right now my SCUBA fins are moving me silently, efficiently around the lake’s shore line. My casts are rhythmic, directional, and searching the water’s depths. The crank bait imitates the shad my quarry feeds on. I am fishing for the lake’s apex predator, Largemouth Bass.

Of all the fish that I have caught, this fish is a very different denizen of the water. The bass is not the “King” (Tarpon) with their towering continuous jump ability; nor the Prince (The Rainbow), with their wide beautiful flashing red side stripe. The bass is the thug, the mugger, and an ambusher and will eat anything they are bigger than. They apply their trade very successfully in the dark. It is dark now.

The bass feeds along a continuum ranging from the gentle flair of his gills, creating a vacuum and sucking their unfortunate prey into their cavernous mouths to slamming anything that moves with the tenderness of a jackhammer. Most fish eat to satisfy hunger and while the bass does this, the bass does something else. They strike out of anger. They react with blinding speed and brute force with actions bordering on hatred.

So much has been written about this magnificent creature. I agree with all of the words used to describe it. What I like most about bass fishing are most people who pursue bass practice catch and release. Bass do not attract the meat fisherman. They are usually too hard to catch. Individuals who eat fish focus on easily caught fish such as the catfish, bluegill or the stocked Rainbow trout.

Catch and release was a natural for me to incorporate into my fishing. I was very young in my fishing experience when I realized fish were not always a renewable resource. The quickest way to ruin a good fishing spot or stop the growth of fish was to add grease. As my love of fishing grew, intentionally killing a fish was like murdering a friend or business associate. It was easy to let the fish go, knowing that it had the opportunity to learn from the experience, becoming wiser, and more selective in its menu choices.

Being more selective means growing into a bigger fish. It is the quest of all fishermen to catch the bigger fish. They are worthy opponents simply because they are hard to catch. There is a sense of accomplishment, a sense of mastery, joined with total exhilaration at the sight and feel of such a fish. I am here for all sizes of bass, but every cast has a personal hope of the larger fish. Hope is a good thing in fishing.

The “Big Dipper” is starting to fade now, yielding to twilight. The hot Arizona sun will soon be completely dominant. The wind switches slightly. My fishing wisdom recalls that the fish always face the wind direction. I adjust the direction of my casts.

I am nearing the dam, with its deeper water, and underwater rock points. I have experience here. I cast to a rock formation. I retrieve slowly, pausing periodically to allow the small crank bait to rise slowly. At the end of one pause, the lure is stopped before it can continue. Built on years of conditioning, the wrist snaps and the rod tip is swept in a low arc. The line tightens, emitting a high pitch whine, the fish is hooked.

The Shimano rod announces its testimony to the strength and power of the fish by bowing elegantly. Its tip nods, bounces and shakes again and again in reaction to the fish’s tenacious struggle against the rod’s restraint. Suddenly, the tautness of the line relaxes as the fish telegraphs its intension to rise to the surface.

The water breaks with the force of breaching submarine escaping depth charges. With gills flaring, head shaking, and tale walking, the fish launches itself towards the brightening skies. I gasp! The fish is large. It lands, spraying water violently against the water’s surface calmness. The fish sounds and races towards deeper water. The reel reaches its preset release point and releases the line with a controlled slip.

When the reel’s drag stops releasing, I apply side rod pressure and start reeling in line, stopping only briefly when the fish surges again the constant pull of the line. I reposition my hand’s grip on the rod’s handle, hoping to ease the pressure being placed on my wrist. The bass races to the left, with the fishing line slicing a “V” in the water. The sudden side pressure causes the tube to rotate. I apply right side pressure with the rod and the fish stops, flounders on the surface before racing in a new direction; right at me.

I reel as fast as I can, trying to erase the slack in the line. Too much slack allows the lure to loosen and possibly shaken easily. I kick my fins strongly, trying to increase the distance between me and the charging fish. It is useless. The line goes slack.

I feel my heart sink as I momentary think the fish might be lost. I must regain line tension, but I realize this is a critical juncture in the fight. I reel line very slowly. I know that when fish do not feel pressure from the line and rod, they often stop, but if tension is regained too fast, the fish can react so quickly to the new pressure that it gives the line a sudden shock and breaks it.

I feel the fish. It is below my tube. I tighten gradually and the fight resumes with another dash. The reel performs flawlessly, its drag releasing before reaching terminal breaking point for the line. I reel again when the drag stops. I am gaining more and more line. The fish begins to tire.

Bass never really quit fighting. They struggle continuously, shaking their head, diving again and again. It is in the last moment of a contest that inexperienced fisherman lose fish, especially large fish. Their enthusiasm to lay their hands on the fish results in misjudging the fish’s reserve ability of unpredictability. This being said, one simply cannot engage in holding a fish forever in their fighting mode. Fish can often fatigue themselves so much they can literally die from the over execration. Catch and release then becomes non-functional because the whole purpose of the concept is for the fish to live.

So the trick is to catch the fish early enough in the contest and in such a fashion that it reduces the fish’s propensity from releasing itself. In most other watercraft, the need to fill this requirement is nicely accomplished with a net. In a float tube, nets are usually not an option. Their bulk encumbers, their nettings tangling with reel handles, treble hooks, shore and underwater cover. Nets in a float do not work over the long run.

The greatest feature about the fishing industry is that where there is a need, there is usually a product invented for it. Such is the case in this situation, the fishing industry has provided. It is called a Boga grip.

It is a stainless steel precision machined jaw gripping tool. Its dual grips are not serrated, but curved at the tips and no amount of pressure can reopen them when the spring loaded trigger is down in the locked position. The trigger is finger operated from any position making easily released and engaged. Its length is less than ten inches and will land any fish. Its handle is foam padded and mildew resistant. It also weights the fish with a surprising accurate scale that is easily read. It is the perfect fish landing tool when I am my tube, especially when the fish’s mouth is loaded with treble hooks.

The rod is doing its job. The fish is tiring quickly. Now is the time! I transfer the rod to my other hand and quickly unzip the compartment housing the Boga grip. I slip my hand into its strapped handle to prevent from being dropped overboard. With the Boga secure, I quickly reel the fish towards the tube. At arm’s length, I extend the Boga towards the fish’s huge open mouth. I release the trigger and feel the grip tighten around the fish’s lip.

I lift the bass out of the water. The Boga registers the weight. Not quite seven and a half pounds. Wow, what a fish! I marvel at its color, its huge mouth and body mass. I reach for my hemostats tangling on a cord around my neck. I quickly removed the crank bait’s hooks. One last look! I turn the fish, sideways and back again, viewing nature’s work with the eye of a true admirer. With a single finger movement to the Boga’s trigger, I release the fish into the water.

The adrenaline is coursing through my body. My breaths are shallow and rapid. My heart feels like it is racing and my hands tremble. I think to myself that the day I stop feeling like this after catching a large fish is the day I stop fishing.

Suddenly, from shore, not too far away, I hear “Hey, mister, what is that you are fishing in?” “Are your feet in the water?”

I answer. “It is a float tube and yes, my feet are in the water” all the while patting my tube with an affectionate “Atta boy!”